Yes, I doubled my stock market earnings during the telecom crash.

More impressive, I managed to do it with poor hearing, crappy vision, abysmal knowledge of financial markets, and having virtually no memory of even pulling the feat off. Oh, and did I mention that I was a newborn? (2 x 0 = 0 for reference).

For a long time, I have been under the impression that asset bubbles were born out of assets that are, well, liked. For example, the World Wide Web is often described as a novelty or a new frontier. It was a unique breeding ground for communities, culture, and conversations near and far at speeds never before seen. The various chirps and quirks of software to hardware were iconic and nostalgic. And although internet hype fueled a financial crisis that opened the 21st century, who could blame it?

The web’s predecessor, artificial intelligence, exudes a completely different vibe. Corporations revere it as a technological revolution, gracing our lives with efficiency and productivity. Yet in conversations, it is accompanied by disgruntled eye-rolls and depressed grumbles. Suffice to say, the hype around AI feels lackluster at best.

At first glance, this observation might seem anecdotal, especially after reading countless headlines of AI overvaluations, corporations touting AI integration, rising debt levels to fund AI projects, and, of course, the AI bubble debate. This disconnect was hard to shake, though: How could AI be a bubble if no one likes AI?

Part I: No one likes AI and the numbers behind it.

The first question to answer was, “Do people really dislike AI?” In my search, I never expected a unanimous disdain for AI, but a simple majority? Shockingly easy to find.

The Pew Research Center performed a study on Americans, ages 18 to 65+, on their views on AI. It is an eye-opening study, but there are a few takeaways that stood out to me:

- A majority population was pessimistic towards AI’s effect on people’s ability to think creatively, form meaningful relationships, make difficult decisions, and solve problems.

- 50% of adults were concerned with increasing daily use, while 10% were excited, leaving the rest equally excited and concerned.

- Only 13% of Americans would be willing to let AI assist them a lot in their daily lives, while the rest would let them assist a little or not at all.

Harvard University also provided another study capturing the generative AI sentiment of Americans ages 14 to 22. Another recommended study, but here is the high-level:

- Only 4% of young people use it daily.

- 41% have never used AI generative tools.

- One third of young people never use generative AI because they believe it is not useful to them.

Menlo Ventures noted that while AI use is growing, it is not certainly not without hesitation.

- 71% Worry about data privacy and security.

- 58% Don’t trust information from AI.

- 63% Don’t see a need to use it in their daily lives.

That said, when it comes to Americans, words don’t break bones, sticks and stones do. AI has faced real-life, bipartisan consequences from locals, activists, and governments alike. As of March 2025, $64 billion in data center development was blocked or delayed due to local backlash. Infrastructure development is smeared with environmental issues, tax abatement opposition, power consumption, and grid strain, leaving local governments with a rare but powerful pushback from both sides of the aisle.

Other trends include newly coined slang, such as AI Slop, Clanker, and Bot-licker, being used to describe the general public’s distaste for AI. Even the Census Bureau has reported that AI adoption rates by firms have recently flattened out. Suffice to say, AI dissatisfaction is widespread.

However, it is still puzzling why a bubble could have inflated in light of weak consumer sentiment. If AI were a bubble, what would be the signs, and does a disconnect like this even really matter?

Part II: No one likes it, so it can’t be a bubble, right?

“The almost singular through line behind every major financial crisis is one thing: debt,” wrote Andrew Ross Sorkin in his new book, 1929.

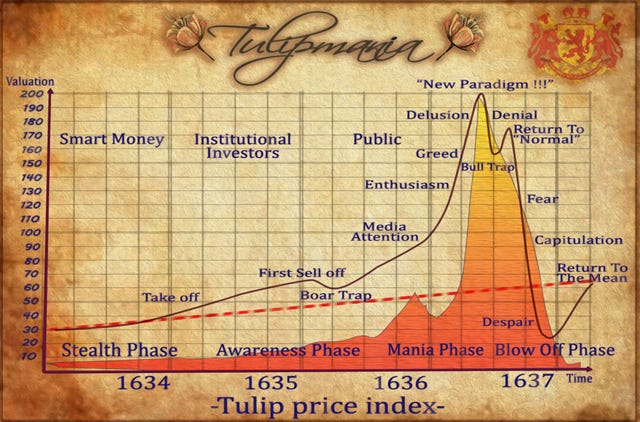

Bubbles have a tendency to follow a similar pattern: investors overreach and overdevelop an asset until fear triggers an avalanche in asset value, evaporating hard-earned funds into thin air. To achieve high levels of overexuberance, financiers turn to the profit and loss multiplier, debt. As for AI, they are far from the exception.

AI-related firms are issuing high levels of debt to finance AI buildout. In 2025, AI-related debt amounted to approximately 30% of total net issuance in the US grade market. The issuance for AI development for the next few years is forecasted to be $1.5 trillion, says JP Morgan. As borrowings increase, so does the rise of sketchy debt vehicles such as SPVs and junk bonds from companies such as Meta and Oracle. If nothing else, debt provides a clear direction for capital spending: a nonstop, pedal-to-the-metal, AI-induced spending rally. To put it another way, debt is an exuberance indicator.

However, exuberance does not make a bubble; it is simply the inflating gas. It became clear that bubbles are born out of some disconnect or misalignment in the financial world and the real world. In this case, the disconnect comes from the violent funding of a product that makes people wildly uncomfortable.

I began this article with one question in mind: How can AI be a bubble if no one likes it? To answer it simply, if no one likes AI, then the future can only be a bubble.

Conclusion

It is easy to conclude that, if the wisdom of crowds is not aligned with the expectations of corporate, a crash is sure to happen. And while it may be true, it felt too basic an ending. Plenty of experts smarter than I are currently predicting the AI Armageddon, so there’s no need to beat a very dead horse. Instead, I wanted to end on a different note.

Martha Gimbel, founder of the Budget Lab at Yale, puts it best: “I think we are really, really bad at predicting the effects of technological disruption on the labor market and also how fast it’s going to happen.” Although she was referring to the labor market, her sentiment reflects a broader theme in AI. The predicted role of AI versus the actual role AI may look very different ten, twenty, or a hundred years down the line.

I believe the discontentment with AI is representative of a few broader truths: The first is that AI has yet to find its place in our society. Secondly, the rise and fall of a tech bubble is, unfortunately, a very human way of finding that place. Thirdly, the overall apprehensiveness of AI seems reflect our innate craving and admiration for human intuition and interaction. If a bubble bursts because of that, it might not be so bad.

Article by Calvin Huang. Read on Substack